Five of the most famous "out-of-place" artifacts on Earth that challenge our understanding of history.

The so-called "out-of-place artifacts" or ooparts (out-of-place artifacts) have been discovered in various parts of the world, challenging historical narratives in some respects.

Out-of-place artifacts are items unearthed by archaeologists during excavations of temples or ruins of ancient civilizations. Their uniqueness lies in the fact that these objects appear to be much older than the time when such advanced civilizations could have existed on Earth.

The term oopart was coined by American naturalist and cryptozoologist Ivan Sanders to describe artifacts found in extremely unusual locations — or items that simply do not fit into the well-known timeline of history.

Here are five of the most iconic artifacts that perfectly fit the definition of ooparts.

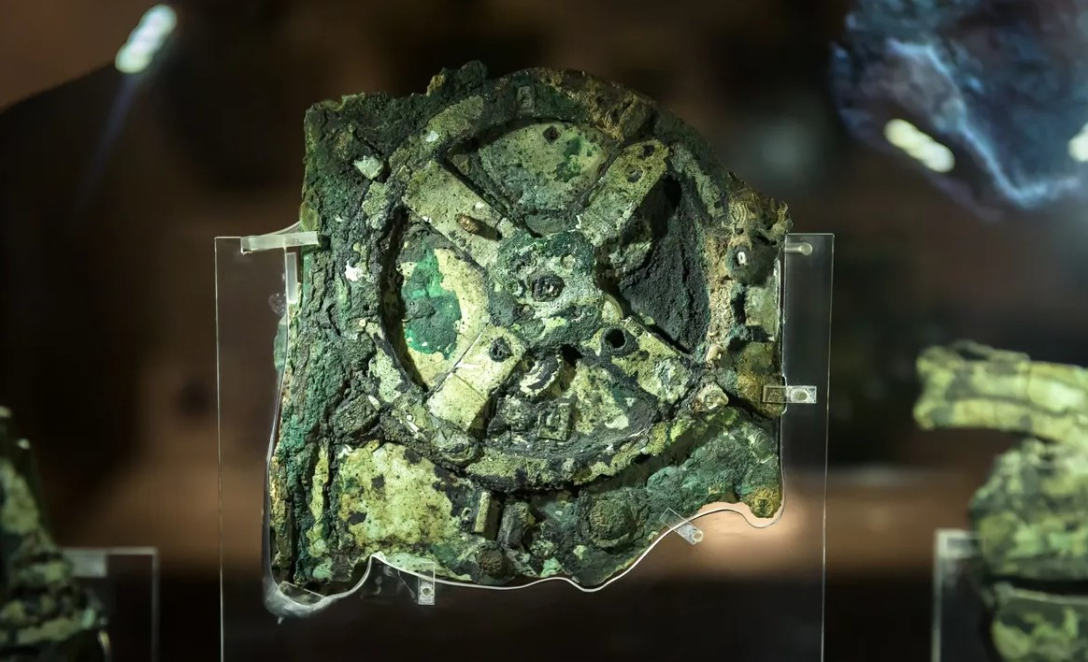

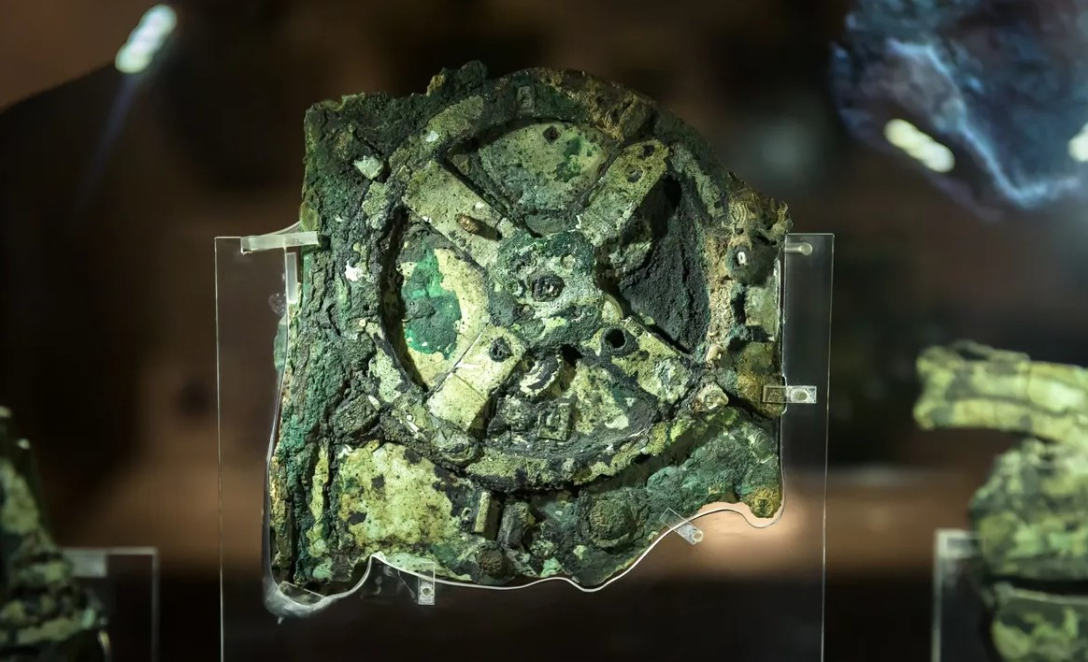

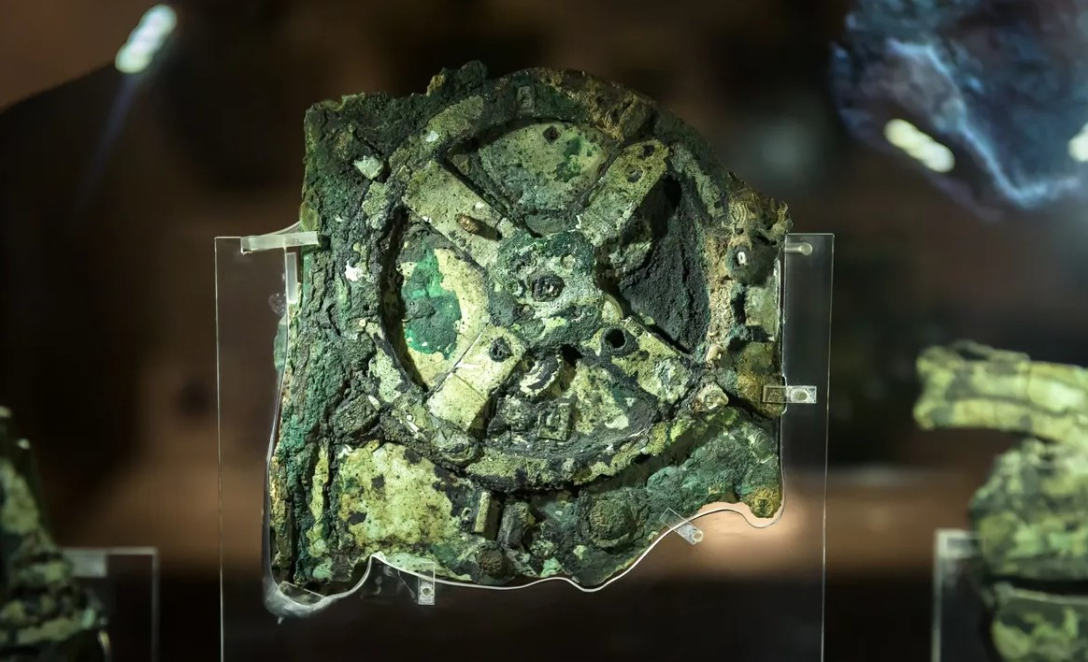

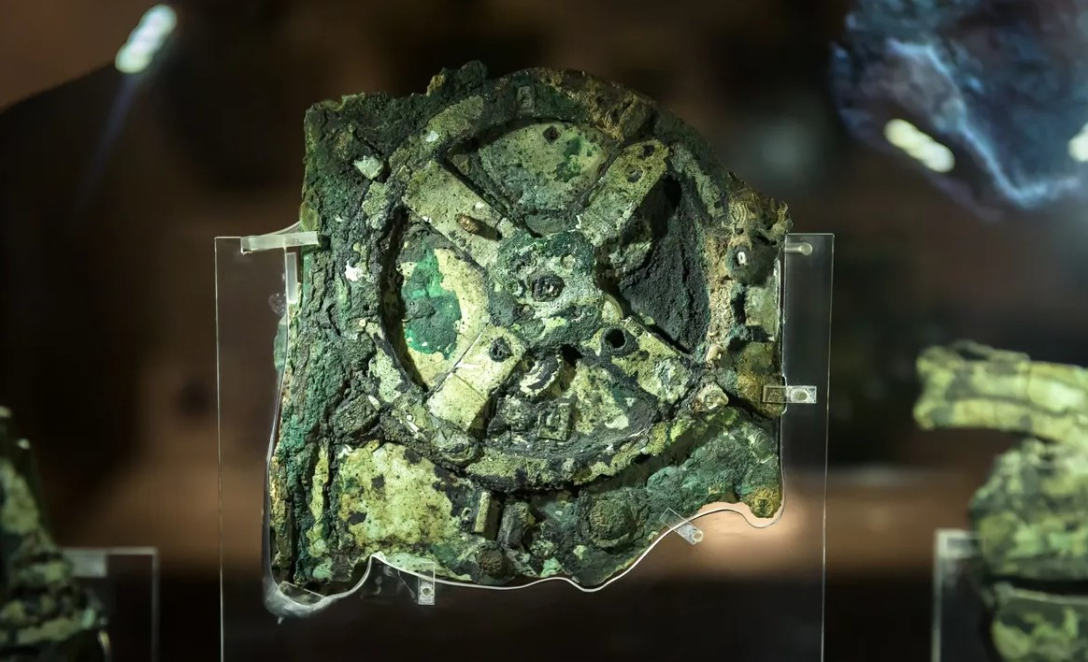

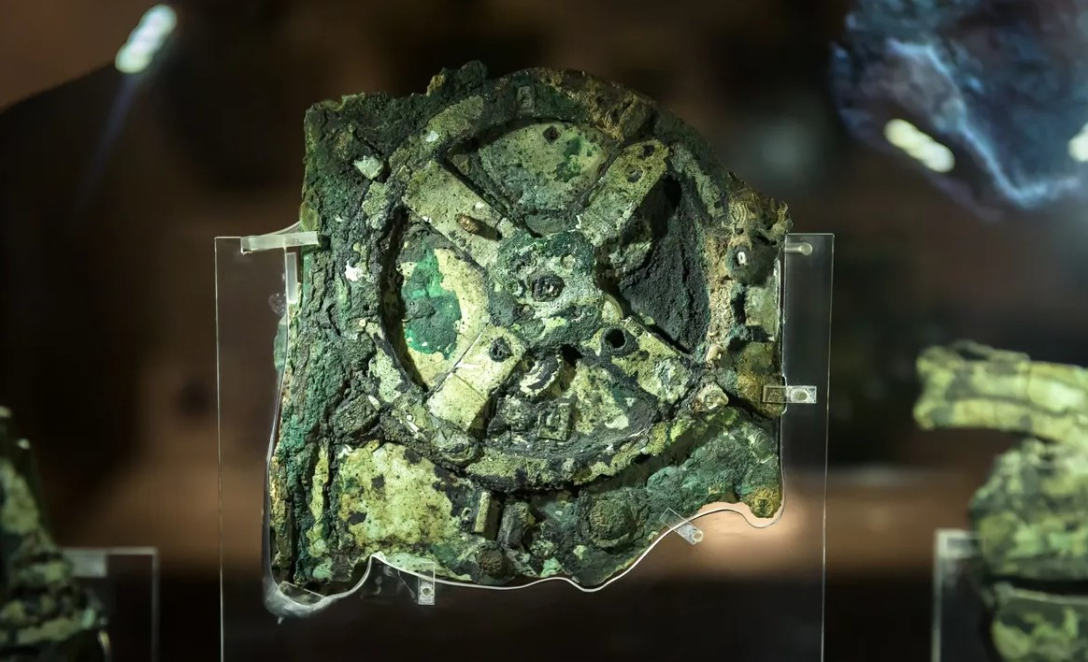

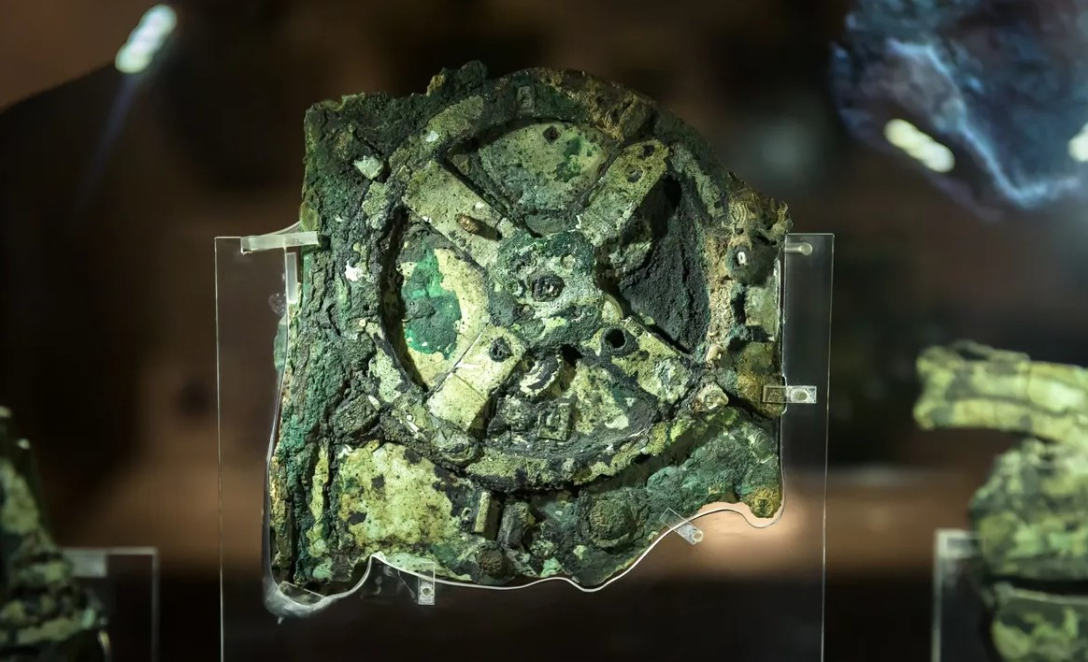

1. Antikythera Mechanism

3

3 In Ancient Greece, something akin to an analog computer was created.

It was discovered in the Aegean Sea and was designed to predict astronomical positions and eclipses up to 19 years in advance for astrological purposes, as well as the exact dates of six ancient Greek competitions, including the four major Panhellenic games.

What’s astonishing is that at some point in history, such technologically advanced devices were simply no longer created. It wasn't until 1600 years later that astronomical clocks appeared in Europe.

2. Maine Penny

4

4 This intriguing coin was found in Maine, in the northern United States. This Scandinavian coin dates back to 1065-1080 AD and belongs to the reign of Olaf III of Norway.

The Maine State Museum and the Smithsonian Institution have recognized it as authentic, suggesting that Vikings set foot on American soil long before Christopher Columbus.

5

5 The reason why this coin was found in pre-Columbian American ruins remains partially unexplained. Some hypotheses propose that this proves contact between Norse explorers and Native Americans.

Other researchers have found a simpler explanation: it is evidence that accidentally ended up at the excavation site, as it is the only item of its kind found there. If there had been such contact with the Vikings, it is likely that other items, not just this coin, would have been discovered.

3. Dorchester Pot

6

6 The Dorchester Pot was an unusual find made in 1851 after an explosion at Meeting House Hill in Dorchester, Massachusetts, in 1852. The pot is a vase or pitcher made of a zinc-silver alloy, standing about 12 centimeters tall and 16 at the base.

The pitcher was found several meters deep, buried under a layer of sediment. The dating method of the time suggested it was 100,000 years old, placing the artifact in the category of oopart.

This vase contained remnants of plant species that went extinct tens of thousands of years ago, as noted by some botanists who studied the artifact.

Shortly thereafter, the prestigious magazine Scientific American published an article about this unique find, describing both the item itself and the peculiarity of its discovery. Initially generating immense interest, the news lost traction due to the overwhelming rejection from the scientific community.

As it moved from museum to museum, the object was ultimately lost, and its whereabouts remain unknown to this day.

4. Piri Reis Map

7

7 This refers to a world map created in 1513. The map contains information that could not have been known at the time of its creation, including Antarctica.

Many theories have been formulated regarding this document. Among them was even the suggestion that the map was copied from Columbus's records. According to legend, Kemal Reis, a member of an Ottoman convoy (a freebooter in the service of his conglomerate), captured seven Spanish ships off the coast of Valencia in 1501.

One of these ships carried a sailor who claimed to have sailed to unknown lands three times under the command of the overconfident Columbus. He held a map drawn by this individual.

After the battle in Valencia, Kemal Reis sent the Spanish prisoner with Columbus's map to his nephew.

That nephew, none other than Piri Reis, used the prisoner’s testimony and the document to chart new islands and coastlines discovered by the Spanish in the Caribbean.

More than four centuries later, in 1929, the son of the grand vizier of one of the last sultans, a historian studying the archives of the Ottoman Empire, found a third part of the map drawn on gazelle skin in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul.

The fragment depicting the shores and islands of the New World is signed by the Turkish admiral named Piri Reis — Reis means admiral — and dated 1513.

This map is said to be the oldest cartographic record of North and South America, the most accurate map of the 16th century, and a copy of Columbus's own map.

However, some assert that it is too accurate for its time, including lands that were not discovered until centuries later.

5. Black Pyramid with an Eye on Top

8

8 This out-of-place artifact was discovered in 1893 in the jungles of Ecuador, Guatemala, and Mexico (where the find was made) along with other similar artifacts cataloged as "Mana artifacts (items with divine power)."

The item is primarily made of stone and stands exactly 27 centimeters tall.

On one side, the stone has a whitish hue, while on the other, it is black, forming a pyramid topped by an eye.

Someone accidentally observed the strange object under ultraviolet light and saw something remarkable: the eye of the small pyramid began to glow strangely, indicating that the material used for the eye was a precious gem.

Currently, the pyramid resides in a private collection, making it impossible to ascertain its exact location.